January 7, 2016—February 13, 2016 | Opening Reception: Saturday, January 9th, 3-5pm

James Harris Gallery is pleased to present Drawings and Objects, the first solo exhibition by Chicago based artist Anne Wilson. For over thirty years, Wilson’s multi-media art practice has engaged with the cultural production of textiles and the sociopolitical framework that dictates and informs such production. As both a textile artisan and conceptual artist, Wilson approaches her work as a process based, repetitive labor while simultaneously addressing the implications of a mechanized global industry. Wilson works in realms beyond her medium as researcher, social activist, and facilitator for social engagement. Drawings and Objects includes a series entitled Dispersions of framed fragments of cloth with holes sewn open by thread and human hair, small thread drawings, and a series of glass works. Wilson’s connection to her materials is both personal and anthropological, considered as products of cultural constructions that can embrace utility, cultural identification and sophisticated aesthetics.

When Wilson began her practice in the 1970’s, artists were just beginning to relocate their work into social spaces outside of the institutionalized art world. Today we have more or less entered into a post-institutional era, where art spaces and social spaces are one in the same, and getting outside of the institution is perhaps a mute point. Wilson’s practice responds to this reality, offering a seamless exchange between these converging worlds. In this sense, her work is at once sculptural, performative, cooperative, process-based, and a demonstration of social activism. Over the past couple decades, Wilson has focused on large-scale projects that take on a “micro-political” approach to art. In her 2010 site-specific project Local Industry, Wilson brought together 2,100 volunteers and 79 experienced weavers to create a community weaving. There is optimism in this form of generative collaboration for Wilson, where a small group (a class, an artist collaborative, an administrative team) becomes “-a microcosm of political tensions and resolutions that are likened to larger political systems.”

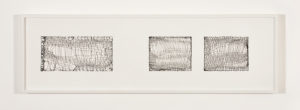

For this show, Wilson has created a new series of Dispersions, a body of work she has developed over the past few years. Wilson refers to these small-scale pieces as “materialized drawings,” made from fragments of white damask tablecloth, and embroidered with thread and human hair. The white tablecloth, typically associated with formality and propriety, is transformed by heavy use and suggests a sentimental personal connection. Human hair has particular significance in Wilson’s practice, a material she has been working with since the late 1980s. Wilson is intrigued by the dichotomous role of human hair, as both a sumptuous expressive material when it is part of a body, but also experienced as distasteful when detached from the body. Wilson negotiates these different territories of meanings and creates new use in her repurposing of these materials into unique beautiful objects by an action of “disrepair”. In this manner, Wilson negates the functionality of the fabric and stitches into the natural flaws and tears to create delicate handmade designs that are reminiscent of a celestial void.

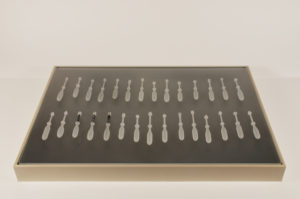

Accompanying the materialized drawings is a group of objects created during Wilson’s residency at Pilchuck Glass School. Remade in glass, the objects are replicas of textile hand tools used to organize small lengths of thread for use in fiber processes. Three vitrines of these neatly arranged tools invite a close examination. From a social perspective, these objects signify issues around a renewed enthusiasm for hand-crafting and tactility (a backlash to today’s highly technologized society), a desire that is met through outsourcing and unregulated globalized labor economies. Wilson is interested in glass as a mediated material, never directly touched by its creator, but also mediated in the metaphorical sense as a cultural construction.

The politics around display is an ever-present consideration that is conflated into the reading of Wilson’s work. The white metal archival frames for her Dispersions is an acknowledgement to conceptual process art in its serial display of the time-based action of needlework, what Wilson refers to as “body-time”. The institutionalized method of display further connects the Modernist history of mark making with the history of needlework. For her objects, Wilson uses glass cases associated with natural history museums and anthropological concerns, an apt vantage point from which to consider this work.

In her dedication to a conscious approach to her materials, Wilson presents an alternative to the current narrative that charts a new history in which craft relations with industry are not opposed. Wilson considers how craft itself performs within her projects, integrating materials that are imbedded with the history of industrial artisans and transforming them in a social space. This trajectory in art was helped defined by Niccolas Bourriaud, whose term “relational aesthetics” has helped to define socially interactive artistic practices that are the result of real gestures in real time, offering ongoing discursiveness rather than the private imaginings of a single artist. The product in this sense has shifted from a representational intention to a socially generative one.

Wilson’s glass objects are made possible through residencies at the Pilchuck Glass School; the Museum of Glass, Tacoma; and RIT, Glass Department. The work was accomplished with the remarkable glass skills of gaffers and artists Jessica Julius, Nancy Callan, Katherine Gray, David Willis, Kimberly Pence, Ben Cobb, Alex Stisser, Conor McClellan, and students from RIT with support from Michael Rogers and Robin Cass. Special thanks to Jessica Julius who was Wilson’s most exceptional artist assistant at Pilchuck.

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

25 1/4" x 25 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

20 3/8" x 20 3/8" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

25 1/4" x 25 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

20 3/8" x 20 3/8" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Thread, hair, cloth, white steel frame

23 1/4" x 23 1/4" x 1 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Glass, thread

3 1/4" x 22 1/4" x 15 1/2"

Inquire about this work

Glass, thread

3 1/4" x 15" x 11 3/8"

Inquire about this work